Fight Somali piracy on land, not at sea

ANTONIO MARIA COSTAÂ Globe and Mail

Why chase Somali pirates for seven hours if you can’t arrest them? Canadian sailors must be asking themselves this question after being in hot pursuit of a Somali skiff in the Gulf of Aden on Sunday, eventually boarding the vessel, disarming the pirates and detaining them. Since the crew of the Canadian warship believed it lacked the authority to make arrests in international waters, the pirates were released – no doubt pleased to regroup and attack again.

Canada is not alone in facing this dilemma. Other governments with vessels operating in these troubled waters have also been at a loss about what to do with captured Somali pirates.

In the old days, you could hang pirates on the spot or toss them overboard. Thanks to human rights, that’s no longer an option. But there are ways of bringing piracy suspects to justice.

Suspects could be tried in the country they came from, or the one that owns the seized ship. But the Somali criminal justice system is weak, and countries such as Liberia, Panama and the Marshall Islands – where many of the ships are registered – face challenges in handling these cases.

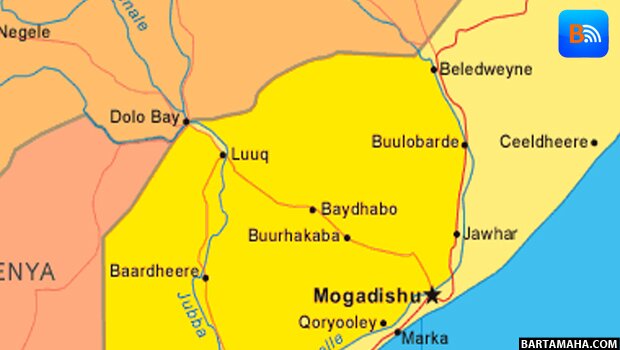

A third, more realistic option is for the pirates to be tried in the region. Increasingly, warships are interdicting pirates and transferring them to Kenya to be prosecuted. It is thus vital to strengthen the capacity of Kenya, and other countries in the region (such as Tanzania, Djibouti, Yemen and Eritrea) to arrest, investigate and prosecute piracy cases.

Where there are concerns about jurisdiction, subject to a special agreement, a law enforcement officer or detachment from, say, Kenya could join a Canadian ship off the coast of Somalia as a shiprider, arrest the pirates in the name of Kenya, then have the ship take them to a Kenyan court for trial.

Depending on the strength and capacity of the enforcement detachment, shipriders could board vessels and begin criminal investigations at sea, including seizing evidence and interviewing under the same legal regime that will apply to any eventual trial. It’s simple, and it works: This practice has proved effective in the Caribbean against drug smugglers, fortified by intelligence, air surveillance and police co-operation.

There is another way to catch the pirates – go after their treasure. Unlike buccaneers of old, Somali mafias are not burying their booty in the sand. In towns up and down the coast (and in neighbouring countries), ransom money is buying houses, cars and power. Profits are invested in satellite phones, GPSs, weapons and fast outboard motors, or to bribe officials and port informers.

This money is hard to track when it is circulating within Somalia’s cash-based economy. But the more ransom collected, the greater the temptation to move money offshore using the hawala system and third parties, particularly in financial centres where shipping companies are located. This makes the criminal groups more vulnerable to detection.

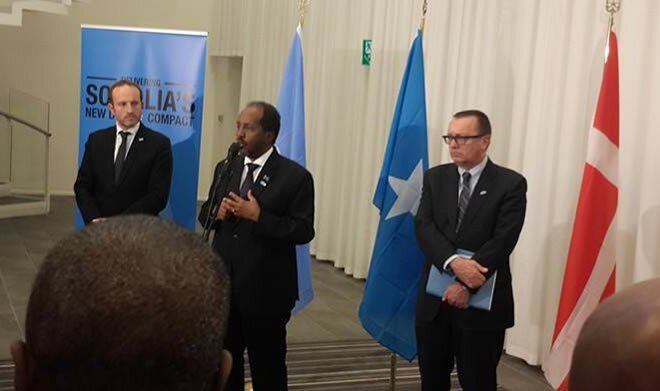

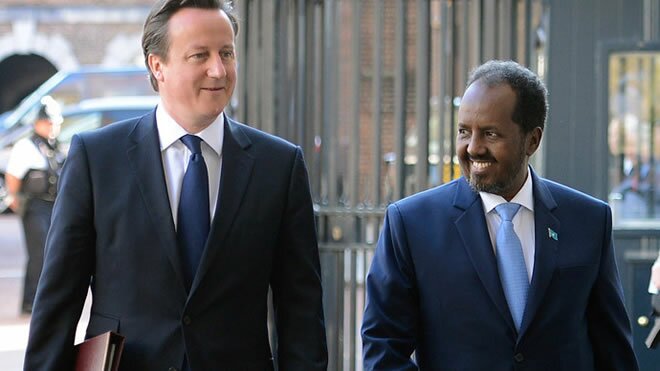

This week, a pledging conference will take place in Brussels to help Somalia’s new government bolster peace and security. A priority must be to rebuild its broken justice system. This would enable the Somali government to enforce the law on its own soil and to tackle the problem of organized crime that is wreaking havoc in the country and off its coasts. Development aid can improve local administration, create job alternatives to piracy and smuggling, and restore much needed social services and infrastructure. Particular attention should be paid to parts of the country where basic institutions are already in place, such as Puntland and Somaliland.

Somali pirates must be brought to justice – and international forces can help. But the world’s navies cannot patrol the Horn of Africa forever. Over the long term, the problem must be solved on land, not at sea. This requires judges and police, not just sailors and snipers. The government of Somalia needs help to restore order and justice to this lawless corner of Africa. If not, commercial shipping will be held to ransom, Somalia will remain a nest of instability, a breeding ground for terrorists and a paradise for organized crime.

Antonio Maria Costa is executive director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar