Rebuilding Kismayo After Al-Shabab

The strategically located port city of Kismayo is becoming a test case for the new Somalia.

Retro white-metal-and-wood hospital beds—arranged in a cluster in the dappled shade of a broad tree—serve as the main emergency ward at Kismayo General Hospital. Emergency is the only kind of care the small team of hospital staff can provide with so few resources. For the past three years they’ve operated under the rule of Somalia’s al Qaeda–linked militants, Al-Shabab. “Explosion wounds and C-sections—that’s all we can cope with right now,” says the hospital director. His charges, 23 of whom arrived on the same day in October, when an IED exploded in town, suffer broken bones and injuries caused by shrapnel. Many also nurse gunshot wounds from stray bullets that government-aligned forces fired in the chaos after the attack.

Retro white-metal-and-wood hospital beds—arranged in a cluster in the dappled shade of a broad tree—serve as the main emergency ward at Kismayo General Hospital. Emergency is the only kind of care the small team of hospital staff can provide with so few resources. For the past three years they’ve operated under the rule of Somalia’s al Qaeda–linked militants, Al-Shabab. “Explosion wounds and C-sections—that’s all we can cope with right now,” says the hospital director. His charges, 23 of whom arrived on the same day in October, when an IED exploded in town, suffer broken bones and injuries caused by shrapnel. Many also nurse gunshot wounds from stray bullets that government-aligned forces fired in the chaos after the attack.

Despite the apparent challenges, the hospital director presents the circumstances optimistically: By “using sparingly,” the hospital has managed to have enough emergency kits to treat the patients who come to the facility—the only hospital not under Al-Shabab control in the region. They do have anesthesia. The hospital recently signed an agreement with the World Health Organization to receive some surgical equipment and medicine—the first international support since Doctors Without Borders was forced to withdraw from the area in 2008 after three of its staff were killed in an IED attack. And two days after The Daily Beast interview, the hospital staff was slated to be paid for the first time by the city’s new post-Shabab administration.

The progress may sound nominal. But it’s emblematic of both the changes and the challenges afoot in newly liberated Kismayo—and an illustration of the level of isolation the people of this port city have endured.

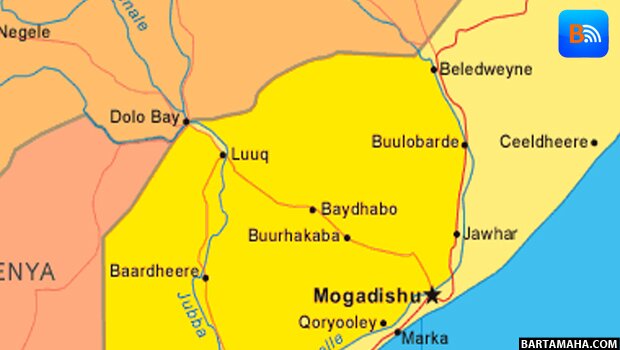

With the territory they controlled shrinking—due in large part to operations carried out by the Western-backed African Union peacekeeping mission (AMISOM)—Al-Shabab consolidated its efforts around Kismayo, Somalia’s second-most strategic city after Mogadishu. Thanks in large part to Kismayo’s port, the militants generated an estimated $25 million in revenue in 2011 from taxes imposed on Somali charcoal shipments, primarily to the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, according to a report published by a U.N. monitoring group in July. Since the production of charcoal in the Kismayo area started around 1997, it has become by far the dominant industry, now accounting for 80 percent of business in the region, local investors estimate. “People in this community were doing the charcoal business since before the existence of Al-Shabab. So the issue isn’t Al-Shabab, the issue is that the businesspeople invested [almost solely] in charcoal because there was a lack of government. There was no control at all, no administration,” says Sheikh Hassan, speaking on behalf of a group of businessmen gathered for a meeting in a warehouse smelling of fish and petrol at the Kismayo port. “They were going for the cheapest business they could invest in so they can get their livelihood.”

What to do with the remaining stock of charcoal—which is barred from export by a U.N. embargo intended to stem Al-Shabab’s revenue stream and prevent deforestation of southern Somalia—is just one of the contentious issues that Kismayo’s new administration and Somalia’s new central government in Mogadishu need to jointly hash out. The charcoal owners say that the stock, much of which currently sits on a vast plot in town in mounds stacked two stories high, is worth $30 million to $40 million—though no one really knows the true value.

“For the moment, there’s no reason for there to be a fight” over charcoal, says a Nairobi-based international Somalia expert, noting that there will have to be a negotiated solution that draws in the charcoal owners and “their supporters with guns.” But he adds that Kismayo’s charcoal stock could spark political conflict. “If the [central] government remains adamant and tries to impose itself without a negotiated settlement, then in the context of the broader Jubba Valley issue, it’s just one more irritant to divide the two sides.”

Those divisions run deep, centering on the question of whether the southern region in which Kismayo sits will be able to establish itself as a semiautonomous state in the post-transition Somalia.

“The Constitution of Somalia spells out federalism as a key component of the administration of the country,” says Sheikh Ahmed Madobe, the commander of the most powerful militia in the region, who currently serves as the head of Kismayo’s governing body. “The central government must recognize that fact.” What that means in practice, according to Madobe’s interpretation, is that the three provinces of southern Somalia, bordering Kenya and Ethiopia, would combine to form the state of Jubbaland, with the power to govern with some level of autonomy from the central government in Mogadishu. There’s no doubt that Madobe, who has traded in his military attire for horn-rimmed spectacles, a collared shirt, and an embroidered Muslim prayer cap, is angling for the top post as governor.

With self-declared independent Somaliland as one model—it announced its breakaway in 1991, even though no other country officially recognizes it—the Mogadishu government fears that granting autonomy to other regions would set a dangerous precedent and dilute its power, right at the time when it is emerging from an eight-year transition and eager to create a cohesive country. The last central government in Somalia collapsed in 1991.

“What the new Constitution doesn’t answer is how these new states are established, if they can be established unilaterally, and who decides who controls them. And that’s the million-dollar question,” says Ken Menkhaus, a Somalia specialist and political-science professor at Davidson College. “It’s one thing to say, ‘Yes, federalism is enshrined in the Constitution.’ It’s another to say, ‘Oh, and by the way, I’m setting up my own state.’”

Madobe isn’t the only one with strategic designs for the region. Kenya and Ethiopia also have strong interests in southern Somalia, having both sent their militaries over the border—the very first such sortie for Kenya—to join the effort to oust Al-Shabab. A committee made up of representatives from the central government in Mogadishu and the various Somali clans living in the region is currently in talks mediated by an East African regional body known as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development to decide how to govern areas after Al-Shabab’s retreat and ensure that they don’t fall into the hands of warlords. For Kenya and Ethiopia, establishing a friendly local administration in the border region is a matter of national security. The challenge is that there are a variety of definitions of what such an administration should look like, leaving Western governments, who are funding AMISOM and largely bolstering the Somali government, in a bind.

“There’s a real dichotomy, because even though a lot of governments would like to see the Jubba Valley stabilized and want to support Kenya and Ethiopia in that endeavor, they also want to be seen as supporting the [Somali] central government. And now it’s not possible to do both,” says the Nairobi-based international Somalia expert.

This multisided power struggle is taking place against a backdrop of major political changes in Mogadishu as well. The end of the transitional government in August saw the bloated, notoriously ineffective Parliament dissolved and a new body created that was half its size in a process that was meant to bar candidates with ties to warlords. That new body then selected Hassan Sheikh Mohamud to be the country’s new president, a newcomer on the political scene with a set of credentials rare among Somalia’s leadership. Mohamud spent the past two decades, while the country was embroiled in civil war, founding a university in Somalia and working for international research and aid groups, including UNICEF. But how that background prepared him to navigate the clan interests and warlordism characteristic of Somali politics is still an open question. While some Somali analysts and international observers say Mohamud has the reputation of being inclusive and willing to discuss, rather than impose, others say that he is trying to make decisions too quickly and needs to spend more time building alliances and buy-in.

“It’s very common for governments in Mogadishu to come to power, and the international community rushes to support them and express appreciation for their authority, legitimacy,” says the Nairobi-based international Somalia expert. “It feels like they have real authority when in reality they’re still living inside an AMISOM created bubble, and they have very little reach outside Mogadishu. The more support they receive, the more money they receive, serves as a disincentive to reaching out and practicing inclusive politics. I think there’s a risk of [Mohamud] falling into that trap.”

Nowhere is that tension more acute at the moment than in Mogadishu’s dealings with Kismayo.

“Kismayo is the big test of the post-transitional government, because it’s far and away the most important of the newly liberated areas, and it’s the first area to be ‘liberated’ since the transitional period ended. And so it begs a whole bunch of questions that didn’t have to be answered before,” Menkhaus says.

But President Mohamud may not have much of a choice when it comes to countering the aspirations of the current Kismayo administration.

“If the central government in Mogadishu does not agree with the federal region we are creating, then it means that the whole government will be lacking legal basis for existence, and the Constitution will be trashed,” says Madobe, who adds that semiautonomous regions have a long history in Somalia. “Therefore, I don’t understand why the central government now has resorted to denying the residents of this region their right, while the residents of other regions have enjoyed rights like this one.” With the majority of the so-called government-aligned forces in the region under his control and strong ties with Kenya, whose Army sees him as its most effective partner in establishing security, Madobe should have no trouble getting his point across.

For now, just two months after Al-Shabab retreated from Kismayo under an assault led by the Kenyan Army operating under AMISOM, Kenyan soldiers work side by side with Madobe’s Ras Kamboni Brigade and the Somali National Army to secure the town, under continued threat from Al-Shabab elements that remain in Kismayo and the surrounding desert. Nearly every night, artillery fire pierces the quiet at the main AMISOM base as troops fire at Al-Shabab scouts to keep them far enough at bay. Generators are powered down shortly after dark, because a single illuminated bulb could prove an obvious target.

Local elders say the city’s residents are cautiously returning after fleeing either Al-Shabab’s draconian rules or the assault by AMISOM and the government forces. But what they discover is a place with very little to offer to help them reestablish their lives. Finding enough food is a challenge after poor weather patterns and years of deprioritizing local agriculture. City services like sanitation haven’t been set up. Health care is practically nonexistent except for the most dire of conditions. Some residents at a meeting hosted by the local administration asked to not be photographed, because they are fearful that Al-Shabab may still return or could employ their underground network to target people who spoke to international journalists. So while the fall of “Al-Shabab’s last stronghold” marked a crucial milestone for Somalia broadly and for the foreign actors long invested in their defeat, Kismayo residents emphasize that they are beginning a new chapter in their struggles—hopefully one with greater promise for the future, but a trial all the same. As one local elder describes it, “Now people are refugees in their own town.”

SOURCE: – The Daily Beast

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar