WHO DUNNIT? Somali pirates not to be solely blamed for growing crisis on the Horn of Africa

A video grab from an undated television footage shows an unidentified pirate speaking directly to camera in the town of Eyl in the north of Somalia. Gunmen from the chaotic Horn of Africa country grabbed world headlines with spectacular November 15 capture of a huge Saudi Arabian supertanker loaded with $10

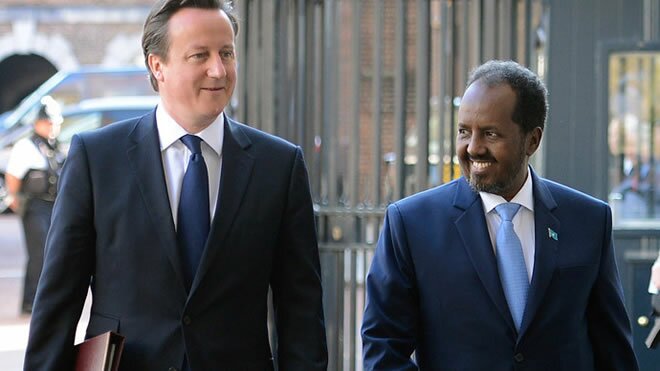

By Peter O’Neil, Europe Correspondent, Canwest News Service PARIS — Somali pirates plundering one of the world’s most lucrative shipping routes, while leading navies from Canada and 16 other countries on costly and often fruitless chases, shouldn’t be taking the full blame for the growing crisis on the Horn of Africa, according to some observers.

The pirates, hardly fitting the storybook image of swashbuckling buccaneers, are easy to demonize, they acknowledge. Many Canadians, who have heaped praise on the sailors and special forces commandos engaged in this deadly battle on the high seas, have said the pirates should be shot on sight or made to suffer more traditional retribution — being hung from the yardarm, keelhauled, or made to walk the plank.

The pirates, portraying themselves as the modern-day equivalent of Robin Hood, say their kidnapping and ransom of ships’ crews is a form of payback for the shrivelling fish catches and environmental havoc after coastal communities discovered drums of industrial and nuclear waste washed ashore after the Dec. 26, 2004, tsunami.

According to some observers, the international community has turned a blind eye since the early 1990s as the impoverished, violence-plagued and largely ungoverned country’s vast, tuna-rich coastal waters were overfished by European, Asian and African fleets and became a dumping ground for Europe’s most toxic pollutants.

A United Nations report revealed that coastal residents suffered a range of health problems caused by exposure to toxic winds after the rusty drums arrived, including acute respiratory infections, dry heavy coughing, mouth bleeding, abdominal hemorrhages, unusual skin reactions and even death.

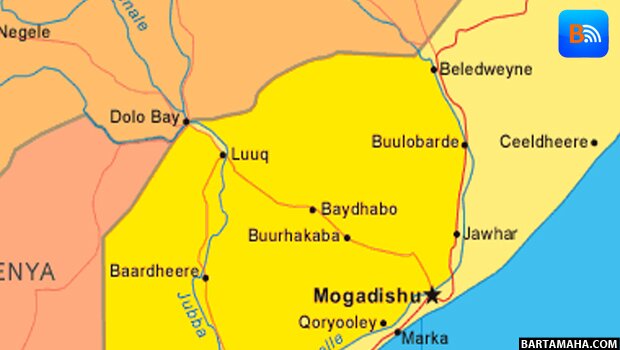

“The western media blame the pirates, which is fair to do,” said Abdi Farah, education minister in Somalia’s semi-autonomous region of Puntland, where most of the pirates are based.

The pirates, he acknowledged, are now part of a sophisticated organized crime network, although he denied reports of bribes paid to the Puntland government.

But he said the current problem is rooted in the frustration and desperation of fishermen who have turned to piracy.

“That aspect has been ignored by the western media,” Farah told Canwest News Service.

Most estimates say the Somali economy has lost more than $300 million U.S. annually due to overfishing that feeds the demand for seafood in the restaurants of London, Paris and Madrid. That perceived injustice allows the pirates to portray themselves as local heroes.

“It’s a very powerful message for the pirates to play back to their communities,” said analyst Roger Middleton, who specializes in piracy matters for the British think-tank Chatham House.

“If they say ‘we’re fighting for you,’ it’s much easier to get the communities to host them.

“I’m not sure that’s the real reason the pirates get into the business. I’m sure they’re much more interested in the fact they can each make $10,000 from a successful raid. But it’s an important motivator.”

He said piracy is linked to the misery associated with a failed state, suffering the kind of anarchy captured in the Oscar-winning 2001 film Black Hawk Down.

“They live in a country that’s incredibly poor, incredibly violent, and their prospects are limited. The rest of the world doesn’t seem to care, certainly from their perspective. It’s very easy to see why they do this.”

Middleton, in a policy paper this week, said the law-and-order issue on the high seas can’t be managed when the host country is in a state of lawlessness.

“Only addressing the root causes, including the internal problems of the country, will offer a way to stop piracy,” he wrote.

Middleton said the short-term goal must be to simply slow down the pace of a problem that is becoming an increasing threat to international shipping, triggering soaring insurance costs and increasing the temptation to find alternate transport routes around southern Africa that will increase the costs to consumers of oil and other shipped goods.

The London-based International Maritime Bureau reported this week that there were 102 piracy incidents in the first three months of 2009, roughly double the incidents over the same period last year and 20 per cent higher than in the last three months of 2008.

The dramatic increase was due entirely to the growing chaos off the Somali coast.

The growth in hijacking attempts has coincided, however, with apparent increased effectiveness in foiling the pirates.

The IMB said one in six ships attacked in the Gulf of Aden in January was successfully hijacked. That rate fell to one in eight in February and one in 13 in March.

The Canadian navy has won favourable reviews for its policing and humanitarian role in the region, with the HMCS Winnipeg temporarily leaving its position as an escort to a United Nations emergency food shipment to spend seven hours recently chasing down a boatload of pirates.

They were finally captured their weapons confiscated, but were then released.

“Canada has really been a force for good in the area,” Ahmed Hussen, national president of the Canadian Somali Congress, said in an e-mail interview.

“As a result of Canada’s efforts, a very substantial amount of food aid has continually reached starving Somalis. One of the sad aspects to Somali piracy is that the pirates have no qualms about hijacking ships carrying food aid to their countrymen.”

Some media reports have suggested that the navy’s hands were tied on the issue of prosecution for jurisdictional reasons, although Middleton said only countries like Germany, with laws that narrowly define justification for arrests in the high seas, face limitations on whether pirates can be arrested.

Canada is part of the UN Law of the Sea Convention, which requires signatories to “prohibit and prosecute pirates wherever they operate,” according to Middleton. The Criminal Code of Canada, meanwhile, says piracy “in or out of Canada” is an indictable offence subject to a sentence of life imprisonment.

But he said North Atlantic Treaty Organization ships and other navies patrolling the area are focused on disrupting the pirates, not taking part in costly and time-consuming prosecutions. There is also the risk that bringing pirates to a western country for prosecution, particularly Canada, could result in refugee claims.

Catherine Loubier, director of communications for Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon, said all countries involved in anti-piracy efforts are “grappling” with issues of jurisdiction over detainees.

She said some countries or alliances, including the European Union but not NATO, have negotiated agreements to transfer detainees to third countries for prosecution.

“As HMCS Winnipeg continues her counter-piracy operations, Canadian sailors will take actions appropriate to the circumstances they encounter,” she wrote in an e-mail Friday in response to specific questions about Canada’s authority to prosecute under the Criminal Code and international law.

“If it becomes necessary to detain individuals, they would be treated humanely, with dignity and in accordance with international law. We are exploring options and seeking advice.”

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar