For refugees in Kansas City, a rough start on new life

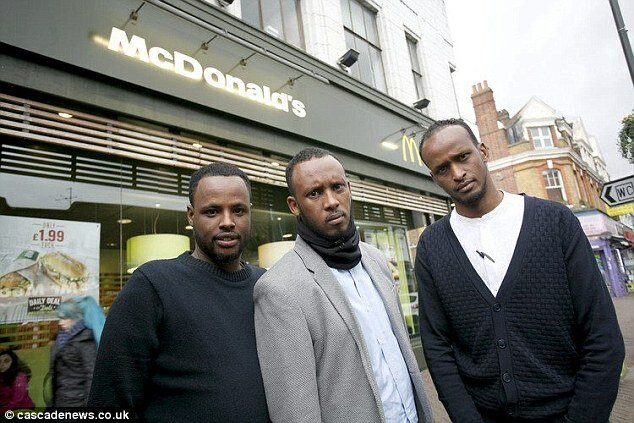

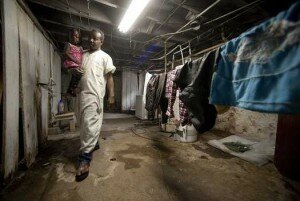

Photo by - Todd Feeback - Elamin Suraj and family, including 2-year-old daughter Muzan, arrived in Kansas City from Sudan and were taken to live in an apartment with problems including a damp, moldy basement. Jewish Vocational Service is working to move them.

In their first month of life in Kansas City, Sudanese refugees Elamin Suraj, Wafa Kut and their three young children had no hot running water.

The Peery Street apartment provided to the family had other issues, too: grime on the walls, basement mold, cupboard doors that fell off the hinges and a lonely couch so dirty that Suraj, the father, refused to sit on it.

“Please take me back to refugee camp if government can’t help me,†he wrote earlier this month to Jewish Vocational Service, the nonprofit agency that brought his family here.

|

Sponsored Link | Somali Youth Summit 2009 Minneapolis

|

The hot-water problem was addressed Friday, and the agency is now working to move the family, given the urgency of Suraj’s written plea: “Cold is killing my children because they are fearing washing in cold water.â€

A mile away on Maple Street, a Somali family of eight — none of them with jobs — faces eviction just five months into their American experience.

“Why do they bring us here if there’s no money to help us get started?†said Asma Siraj, 21, whose siblings share two apartment units, one in which the fourth and fifth months’ rent are overdue.

A grim economy has helped create what Jewish Vocational Service executive director Joy Foster calls a “perfect storm†of struggle for recently arrived refugees in Kansas City.

As the agency gropes for funds and loses longtime employees, the refugees it serves cite a litany of basic needs unmet, housing bills unpaid, medical care neglected.

JVS, established 50 years ago to assist Holocaust survivors, is not the only group buckling under the demands of a nation committed to providing new lives to victims of war and political persecution. As news reports of refugees facing eviction and homelessness mount, many agencies are scaling back resettlement services, telling the government they can take in no more.

The Somalis on Maple Street have tried to find work. Asma Siraj has filled out 10 job applications at restaurants, hotels and schools, all without success.

Her older brother Bakari said, “If just one of us had a job, it would make a big difference.â€

But even in a sour job market, federal authorities expect resettlement groups such as Jewish Vocational Service to cover refugees’ essential needs for up to six months, if need be.

“These groups are signing a cooperative agreement based on the idea that they will make these payments,†mostly through private fundraising and matching grants, said U.S. State Department spokesman Todd Pierce. “Otherwise they wouldn’t be accepting the refugees.â€

Having taken in 205 refugees since October, Jewish Vocational Service will be accepting 61 more in the next three weeks.

Foster said the agency has never been so financially strained in the 11 years she has managed it.

“This is not normal for JVS,†she said. “I’m in a position where I hate to say no … but we’re running out of money.â€

On the other hand, “we don’t want to stop refugee services,†she said, “because these folks desperately need America to do this for them.â€

Getting stretched

In years past, refugees routinely found work in a few months and needed little assistance thereafter. But the slow economy has drawn out the average duration of joblessness for refugees nationwide to about 200 days, resettlement groups say.

That requires agencies everywhere to stretch State Department allotments of roughly $900 per refugee to cover longer periods of need.

When private fundraising and other government grants fall short, families such as the Sirajes on Maple Street are left with finding ways to pay their own rent months before they were expected to do so.

“The landlord is waiting for payment, and we’ve got no place to get the money,†said Bakari, who arrived in late December after having lived with his siblings in Somali refugee camps since 1993. “We get food stamps, and what little we get from welfare takes care of the laundry.â€

The agency has provided video equipment to a deaf sister so she can learn sign language. Through emergency funds secured through the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation, JVS has sent checks to the landlord that it thought would settle the family’s debts, Foster said.

Kansas City’s Somali community also has given the Sirajes some assistance, but all in all, “this life is not what we were expecting,†Bakari Siraj said.

“In Africa, we thought America is a better place where everything can be found.â€

The agency’s resettlement manager, Abdi Mursaal, said the family can hope that an ever-growing waiting list for public housing shortens.

“We don’t want our clients to be homeless,†Mursaal said. “We’ve never had that situation before … but it may happen this time.â€

He added: “We need to rethink taking a lot of people.â€

On the Kansas side, resettlement of refugees is handled through Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas. Its president, Jan Lewis, said she can empathize with any agency struggling to meet the needs of the area’s swelling refugee population.

Because larger cities such as Detroit and Atlanta have told federal officials to send no additional refugees, the State Department has ramped up expectations on communities such as Kansas City, where low housing costs are appealing, Lewis said.

“Last year, they told us we’d get 150 refugees, and we wound up taking in 317,†Lewis said. “This year, if we took in all that the government wants us to take, we’d be getting 500.â€

Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas has agreed to accept about 350 this year and recently told the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops — one of nine groups nationwide that allocate refugees — it must stick to that agreement.

“Especially agencies that are faith-based, like us and JVS — we’re expected to have open arms,†Lewis said. “Catholic Charities has had to say ‘no more’ to this onslaught.â€

The U.S. Committee on Refugees and Immigrants, which funnels refugees to Jewish Vocational Service, recently monitored the Kansas City success rate in the agency’s use of matching grants and found JVS to be performing better than average.

“We have a lot of confidence in JVS,†said the committee’s president, Lavinia Limon. Citing the Obama administration’s decision to provide resettlement agencies an additional $5 million for housing, Limon said, “In a month or two, we should have money to give to Joy (Foster) and get some rents taken care of.â€

Adding Iraqis

By order of the Bush administration, 17,000 Iraqi refugees are to locate in America in 2009.

Fifty-six have been brought to Kansas City in the past eight months by Jewish Vocational Service. No other country produced more refugees to the area in that time.

One of the Iraqis, Emad K. Hussan, is still waiting for someone to pay a $1,200 medical bill from December.

Days after his family was placed in Kansas City, North, Hussan’s 5-year-old daughter broke her arm. “We called JVS and nobody came†to take her to a hospital, Hussan said through an interpreter. “After three days, we finally found a ride.â€

Hussan spoke to The Kansas City Star in the apartment of the refugee family of Zuheir Rofa Homs, who lost his right foot fighting for Iraqi security forces alongside U.S. troops.

He hoped to get a new prosthetic foot upon arriving in America but had to settle for a pair of crutches. Stubbornly keeping the crutches in a closet, he will hop around his apartment on one foot until someone from JVS takes him to the hospital, he said.

The Iraqi refugees, said Foster, make up “one of the most challenging groups I’ve ever seen. …

“Many of the Iraqis come from means and, here, we have some folks turning down jobs,†she said. “We try to tell them, you have to take a job, even if it may not be the ideal job.â€

Foster said the agency would work to address the grievances voiced to The Star. But for the time being, “we have to make judgment calls on which family is the neediest. …

“I don’t like any of this. I feel bad for everyone. I feel bad for my staff, working around the clock.â€

At least two top directors at the agency tendered their resignations this spring, citing management decisions and their impact on the clients.

‘Just a clean place’

For Suraj on Peery Street, the first sign of trouble in his family’s relocation came April 17, when nobody met them at Kansas City International Airport.

“I happened to find a Sudanese cab driver who took me to the JVS offices,†he said through an interpreter. (The agency’s director said the family’s flight arrived 40 minutes early; a caseworker showed up at the scheduled time and even waited two hours.)

The two-bedroom house for Suraj’s family of five was filled with debris when they arrived, said Mohamed O. Aburus, a local Sudanese activist who directs the Sudanese American Center.

Water covered the basement floor as they tried to hook up a washing machine. That’s when plumbing to the water heater broke.

They had been boiling their wash water for four weeks before Foster, alarmed by The Star’s findings, visited the home Friday and made sure the plumbing was fixed.

Elamin Suraj wrote to JVS: “Dirty water is flow everywhere and smelling bad. … I don’t know how to speak English. My Sudanese friend who speak Arabic and English help me to translate my problems in writing. …

“I was not given good furniture. I go to trash and collect some furniture for me because I am desperate. I protest but my caseworker say housing will bring better things.â€

Aburus has become the family’s lifeline in Kansas City. He helped them clean the house, stacking the litter that greeted them on the curb.

“I know the economy is hard on these agencies bringing people over,†Aburus said. “But is it too much to expect to have a clean place when you get here? Just a clean place.

“You and your family have just traveled from the other side of the world. You’ve got nothing. You don’t know the language. The first thing you’re hoping to do is to just relax.â€

But Elamin Suraj refuses still to rest on that couch.

To reach Rick Montgomery, call 816-234-4410 or send e-mail to [email protected].

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar