Exclusive: Former Somali fighter warns of growing radicalism in Canada

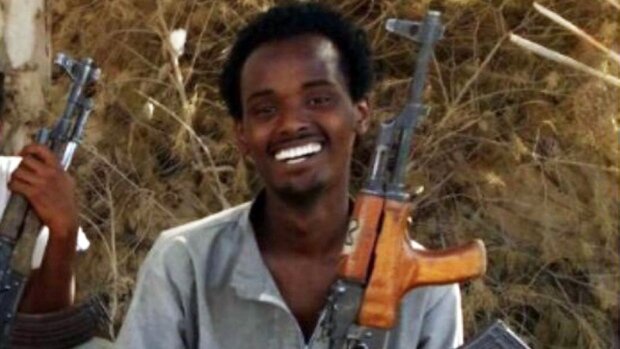

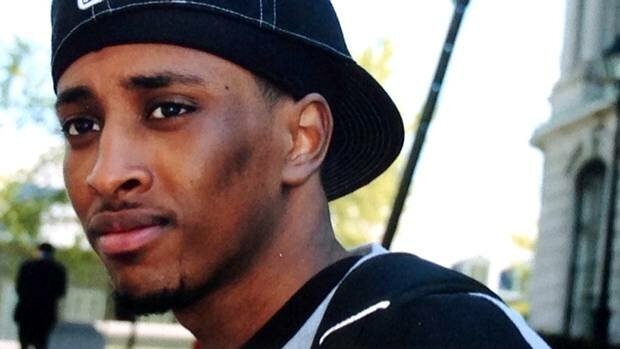

Bartamaha (Toronto):- Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed works as a security guard at an apartment complex in Toronto’s Little Mogadishu neighborhood. It can be a slow job, sitting at the gatehouse, but nobody could call him inexperienced.

Before he returned to Toronto last year, the 35-year-old Canadian spent six months with the Somali militant group Al-Shabab. He trained at Al-Shabab’s main camp in Mogadishu and guarded the frontlines.

“To us, the local people, they were freedom fighters,” Mr. Mohamed said of Al-Shabab. “They were fighting for our country, they were fighting for the survival of the Somali race, and everyone rallied behind them.”

Vic Toews, the Public Safety Minister, announced last week that the government had added Al-Shabab to Canada’s list of outlawed terrorist organizations. He said the al-Qaeda-linked group was “actively recruiting within the Somali-Canadian community.”

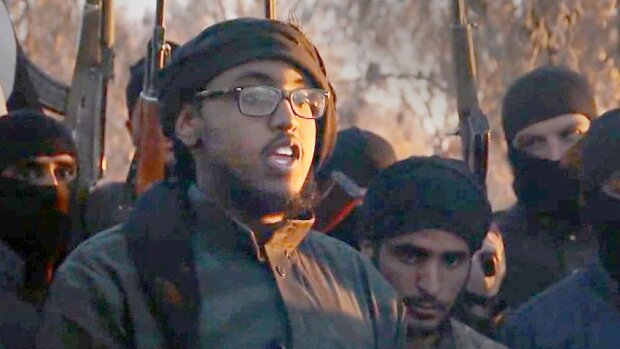

Police and intelligence officials are investigating a half-dozen young Canadians suspected of having joined the militant group. A video posted on the Internet this week claimed one of them, Mohamed Elmi Ibrahim, had died “in battle.”

Mr. Mohamed, who immigrated to Ontario in 1989, is believed to be the first Canadian to speak publicly about his time with Al-Shabab. He told his story to the National Postin exclusive interviews in Mogadishu and Toronto.

Video: Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed speaks out

Mr. Mohamed said he opposes Al-Shabab’s extremist ideology and only trained and fought alongside the group to expel Ethiopian troops from his country. But his time with Al-Shabab gave him a rare look inside the group, now a top priority for Western counter-terrorism agencies.

Mr. Mohamed said Ottawa is right to be concerned. He said that is why he decided to speak out, because he wants to help tackle the extremism that is luring some Somali-Canadians to join Al-Shabab, and that could motivate others to commit terrorism in Canada.

“Young and angry Muslim Canadians. That is a recipe that al-Qaeda would dream to have. It’s like the Lotto 6-49 for them because that’s all they want, to tap into that,” he said.

Because of the chaos in Somalia, some parts of Mr. Mohamed’s account could not be verified. But he provided documents to back some elements of his story and members of the Somali community and two Western officials vouched for his credibility. He was also hired temporarily by NATO last fall to advise the alliance on Somalia.

“I know his story quite well,” said his longtime friend Robert Lemstra, who went to Brock University with Mr. Mohamed and now works as an Africa specialist in the Netherlands. “Him and I have had regular contact throughout the years.”

Mr. Mohamed first came to the Post’s attention in January 2007 in Mogadishu, where he is a member of one of the city’s most powerful clans. The newspaper hired him on one occasion to help arrange interviews with Somalis.

Mr. Mohamed is the son of a tribal chief who owns a Mogadishu auto shop that specializes in Italian FIATs. The family was well-off by the standards of Somalia but when he was 14, his mother died in a house fire and he was sent to Toronto to live with an aunt.

After graduating from Kipling Collegiate Institute, he majored in political science at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont., before moving to Australia to study law at Bond University.

In 2004, he returned to Africa to campaign for his cousin, Hussein Aidid (the son of Somali warlord Mohamed Farah Aidid), who was running for president. Mr. Aidid lost the election but was named deputy prime minister and asked Mr. Mohamed to serve as his political secretary.

During the years Mr. Mohamed had been away in Canada and Australia, Somalia had collapsed. Rival warlords had reduced Mogadishu to rubble and an extremist group called the Islamic Courts Union had emerged from the mayhem.

The ICU sought to restore order to the country by imposing its harsh version of Islamic law. Backed by a Taliban-like militant group called Al-Shabab, Arabic for “The Youth,” it began fighting to topple the government.

As the armed Islamists advanced, the weak Somali government asked its northern neighbour, Ethiopia, for help. Ethiopia had fought bitter wars against Somalia, so when Ethiopian troops arrived to quell the insurgency, the Islamists had no trouble recruiting.

“Ethiopia was basically a God-given gift,” Mr. Mohamed said. He called the decision to allow the Ethiopian military into the country “the stupidest thing they could have done.”

The Ethiopians were implicated in rapes, looting, executions and indiscriminate firing in populated areas. In 2007, Ethiopian soldiers came to Mr. Mohamed’s home to take him away. He was convinced he was going to be killed, but during a skirmish, he escaped into the area of Mogadishu controlled by Al-Shabab.

He said that after his close call, he vowed to fight the Ethiopians until either they left or he died. He said he underwent weapons training at the Salahedin training camp, located in an old Italian graveyard. “It was run by the Shabab,” he said. “From morning until mid-day they give you training, military training – defensive tactics, how to shoot a gun, basic self-defensive training, and in the afternoon they were giving us speeches.”

The Al-Shabab leaders framed the conflict in religious terms, saying Somalis were being punished for not following their Islamic faith, and that if they died fighting for Allah they would go to paradise, Mr. Mohamed said.

Mr. Mohamed gave some speeches himself. Because he had been freed from the Ethiopians as a result of an Al-Shabab attack, he was used for propaganda purposes and was regularly asked to speak to the young militants, he said.

In his speeches, he said, he appealed to Somali patriotism by mimicking lines fromBraveheart, which he had seen at an Ontario movie theatre. “I was basically calling people to unify and forget about the differences of tribe, religious allegiances. I was telling them our country is under occupation,” he said.

Said Mr. Lemstra, “He’s quite a Somali nationalist, as most Somalis are, but definitely not a fundamentalist Islamic person whatsoever. He in fact just wants Somalia to be run by Somalis and have a good nationalist government.”

That sometimes put him at odds with Al-Shabab. He said he once challenged an extremist cleric over his views on martyrdom. And one afternoon, he said he gave an unwelcome speech near the National Stadium that served as the main Ethiopian military base. “I said, ‘I don’t care whether you are a Christian or a Jew or a Muslim. As long as you are a Somali, that’s all that matters now.’”

Afterwards, Al-Shabab took him aside and told him not to say such things, he said. It was a sign that Al-Shabab had its own narrow agenda but at the time Mr. Mohamed wasn’t thinking about anything but fighting the Ethiopians.

Mr. Mohamed said he saw “a few” foreigners in Al-Shabab. Most were Arabs from the Persian Gulf region, as well as Pakistanis and Eritreans, but he said he also spoke with a former Seattle barber who had converted to Islam and had come to Somalia for jihad. He said the barber was later killed.

For six months, Mr. Mohamed said, he went to the Salahedin camp almost daily. “I did a lot of guard duty, facing the stadium most of the time because the stadium in Mogadishu was the biggest military base of the Ethiopian army,” he said.

Asked if he had ever fired his weapon, he said: “Of course. A couple of times they [the Ethiopians] tried to run over us but we defended, and that’s normal, because they wanted to come and just slaughter us.

“We had women and children in the area and if they come, they will do whatever they want to them. So I have my wife and my son in there. Do you think I will allow them to walk [in]? First, they should kill me.

“Because if they go in they will rape my wife and kill my son probably. So I have to do whatever I can to defend, that will never happen and I did whatever I could. I am proud fighting against the Ethiopian army. I’m honoured.”

In 2008, Mr. Aidid asked Mr. Mohamed to come to the Eritrean capital Asmara to help with a new group called the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia. He said he served as chief of staff to the central committee chairman.

When Ethiopia finally pulled its last troops out of Somali in 2009, Mr. Mohamed said he quit within 24 hours and, after spending a few months in Dubai, returned to Toronto to find a job and sponsor his family to join him in Canada.

Upon returning to the Dixon Road neighborhood where he grew up, Mr. Mohamed said he was alarmed at the level of extremism he witnessed among some of the young Somali-Canadians he met. “I was shocked how deep these kids are into this radicalization.”

Some were interested in fighting in Somalia, he said. One of the members of the Toronto 18 terrorist group was Somali-born, and one of the most prominent Al-Shabab leaders, an American named Omar Hammami, had lived in Toronto’s Little Mogadishu.

Then last fall, Canadian authorities began investigating the “Somali Six,” a group of young Toronto men in their mid-20s who may have joined Al-Shabab. Mr. Mohamed suspects a recruiting network may be operating.

“How did these six boys get a ticket, airplane ticket, somebody waiting for them at the airport in Nairobi, putting them in a hotel there, taking them up to another city, taking them out of the country, smuggling them to Somalia? There must be an organization here, there, everywhere.”

He believes youths are becoming radicalized partly from the Internet, particularly by watching online extremists like Anwar Al Awlaki, an American-born al-Qaeda ideologue who encourages Muslims to commit terrorism in Western countries.

Mr. Mohamed is trying to help.

He is in the early stages of forming a non-profit organization called Generation Islam, which will steer Somali-Canadians away from radicalism. He wants the government to contribute funding. No such program currently exists in the Somali community.

“I think this will be an initiative which can really make a difference,” said Mohamed Gilao, executive director of Dejinta Beesha, a Toronto-based settlement services organization that works with the Somali community.

Ahmed Hussen of the Canadian Somali Congress said the fact that just six Somalis are suspected of having joined Al-Shabab suggests that only a small minority are buying into extremist ideology. “It’s not pervasive, however one is too many.”

Mr. Mohamed said his priority is to “help de-radicalize these young kids who are being brainwashed … to tell these young kids that there is another way. You can be a patriot, but you don’t need to be a terrorist.”

He said he fears what could happen in Canada if nothing is done. At the same time, Somalia does not need more gunmen, he said. It needs educated Canadian Somalis to help rebuild the country after three decades of wrenching war.

—————

Source:-National Post

[email protected]

Stewart Bell, National Post Published: Thursday, March 18, 2010

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar