What’s Drawing Somali-American Teens To Foreign Militant Groups?

Istar Abdi, right, a member of the Minneapolis Somali community, right, shakes hands with U.S. Attorney B.Todd Jones, left, after a federal jury in Minneapolis on Thursday, Oct. 18, 2012 convicted Mahamud Said Omar on all five terrorism-related charges of helping send young men through a terrorist pipeline from Minnesota to Somalia.

MINNEAPOLIS — Abdi Mohamed Nur, a 20-year-old Somali-American, reportedly left his family in Minnesota to travel to Syria to join and fight alongside the Islamic State (formerly known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS) last month.

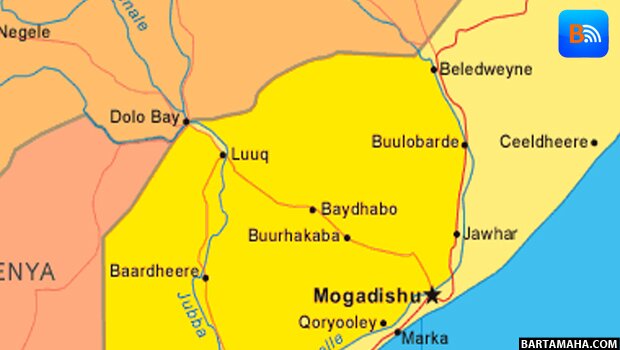

Earlier this month, the FBI’s office in Minneapolis said Nur and about 15 other people from Minnesota drove to New Jersey, where they boarded a flight to Turkey. From Turkey, Nur then allegedly made his way to Syria, and the others to Somalia.

Despite the size of the group and the FBI’s involvement, though, few organizations have acknowledged the situation. The leader of the Somali Citizens League, based in Minneapolis said the FBI has not discussed details of the case with the organization.

“About these kids that left [Minnesota], as a community and citizens, of course it concerns us. The security and protection of our country, the U.S., it is our obligation,” said Jibril Afyare, president of the Somali Citizens League, to MintPress News. “Therefore, these alleged 15 kids that left — we don’t know. We have not seen any evidence that, indeed, they have left. We have not seen any evidence that, indeed, they are there.”

Joining distant wars

After Nur left home, his sister, Ifran Mohamed Nur, contacted the FBI to report her brother missing. Two days later, the FBI told her that Abdi Mohamed Nur was in Turkey and that he was suspected of joining jihadist groups in Syria.

The news has unsettled Minnesota’s Somali community, which is also grappling with rumors that teens are being recruited by sheiks in Somali-American mosques in the Twin Cities. Earlier this year, it was also reported, though not yet confirmed, that Somali-American youths were involved in the Kenyan shopping mall attack claimed by al-Shabab.

For years, the large Somali-American community has served as a recruitment ground for terrorist groups — a trend that is now a major challenge for both the FBI and the Somali-American community in Minnesota. Since 2008, more than 20 Somali-Americans have left the Twin Cities to join the Somalia-based al-Shabab militant group.

This is eroding the positive image of many Somali-Americans who are simply trying to settle down after fleeing the years of political instability and carnage that have plagued their homeland. Many born in the U.S. are caught between two cultures: one that is politically chaotic — Somalia — and another that is organized and has laws in place for redress — America.

“The Somali-Americans in the U.S., especially in Minnesota, have contributed a lot in terms of the economy and the political process,” said Afyare. “We just elected the first Somali councilman to the City of Minneapolis. … We are a better society, we have brought a lot into this state and into this country — the U.S.”

Many teenagers — unemployed and lacking money — are targeted by Islamist militant groups with religious and patriotic appeals. Many Somali-American teens still call Somalia home, and they are urged to return and help fight for their country and against its perceived enemies.

This is why Afyare says now is the time to unite Somalis in Minnesota to fight against militant recruiters such as al-Shabab.

“We need to come together as a country and work on what unites us instead of what divides us,” he said.

A lost generation

Known to the community as a “lost generation,” many Somali-American teenagers want to be part of the changes in Somalia but still embrace American life. Most of them are the children of Somali refugees who fled the country’s long bloody war in the 1990s, and the new generation of Somali-Americans are having trouble assimilating in their adopted home.

Community leaders believe Somalia’s long civil war, clan politics, and resettlement program to the U.S. have all contributed to a disruption in the traditional Somali family structure. For example, many of the young Somali-Americans — like their peers still in Somalia — lost their fathers in the civil war.

“The family structure is broken down,” said Saad Samatar, chair of the Horn Development Center, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit. “Single mothers are running the families, thus they can’t control the boys. [T]he father-figure is missing in the equation of the Somali family.”

In recent years, there have been many changes — both socially and politically — in Somalia and in the U.S. It’s now a race for many young people to catch up with developments in both countries, fit into both systems, and simultaneously satisfy the needs of both countries.

“They are part of this country [the U.S.], but fighting in other countries,” Samatar said. “For many of these teenagers, they are being indoctrinated and brainwashed by some of the extremist groups.”

Ka Joog, a group that promotes the arts in Minnesota’s Somali-American community, told MintPress last year that al-Shabab and other militant groups manipulate disaffected teenagers. These militant groups have employed a mix of religious propaganda, nationalism, and, to some extent, deception to recruit the more than 20 Somali-Americans youths from the Twin Cities to fight against foreign troops in Somalia in the past.

Analysts in the U.S. and abroad have also observed that it will be difficult for Western authorities to stop recruitment, since al-Shabab and other groups constantly try to reach out to youths that feel unwelcome, insulted, and discriminated against in the West.

“They feel that people don’t respect their culture and their values and their beliefs,” Mubin Shaikh, a Canada-based Muslim scholar who infiltrated radical groups while working for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, told Voice of America. “So it’s very easy for them to push away, to not feel they are citizens here [although] they live here. So the lure is with this group that offers them some meaning, some identity, something to be proud of.”

Meanwhile, Samatar also added that the lack of understanding of what it means to be a U.S. citizen contributes tremendously to the identity crisis felt by younger members of Minnesota’s Somali community.

For Somali activists, the question now is: How are the community’s young people slipping away from the Twin Cities to participate in faraway wars? A week before the FBI turned its focus on Somalis in Minnesota, Moner Mohammad Abu-Salha, of Florida, was reportedly the first American citizen to have carried out a suicide bombing in Syria’s three-year civil war.

In light of the recent string of disappearances, the FBI, through its website, has asked the public to provide information on anyone known to, or suspected of, traveling to a foreign country to participate in armed combat — for example, those traveling to Syria to participate in the fight against President Bashar Assad.

Division and chaos boost recruitment efforts

This has all weighed heavily on Somalia’s political problems, as the international community continues to pressure the Somali government to contain al-Shabab and al-Qaida affiliates. In the Twin Cities, however, the Somali-American community is more concerned about their children and the trend of young people leaving to go fight wars abroad. Some have different views and perspectives on how the young people of the Somali community are being recruited by local and foreign terrorist groups both formerly and currently affiliated to al-Qaida.

“[A]s concerned citizens, we would like to cooperate with the authorities to help the parents. As a community, we would like to come together for the protection of our children, and our country — the U.S.,” Afyare, of the Somali Citizens League, said.

Within the community, there are signs of a division that is making it difficult for many to work on common ground to contain foreign extremist organizations recruiting Somali youths from Minnesota. Many in the community, including Afyare, believe that reconciliation for Somalis at home and abroad needs to take place.

The unstable situation in Somalia drives Somali youths in the U.S. and abroad to join warring factions in Syria and other countries in political turmoil, according to Afyare.

“Somalis need to come together. We need to work on our problems. We need to work on the security of our country. We need to make sure our youths are educated,” said Afyare. “To reach that, true reconciliation must take place. There are victims, there are people that have been hurt. Like South Africa, everybody has been through this.”

FBI investigates

As the FBI continues to investigate whether young people from the Somali-American community are fighting in Syria, leaders in the community say the FBI met with some of of them at the Brian Coyle Community Center on June 12.

“We are reviewing the information… to identify persons who may have traveled, and persons who may have intention to travel [to Syria],” Kyle Loven, FBI chief division counsel in Minneapolis, told the media. “We plan to actively engage with the community to identify at-risk youths who may be considering travel to fight in Syria.”

The FBI stressed that most of the young Somali-Americans are reportedly recruited to join foreign terrorist organizations. Thus, according to Loven, the FBI is trying to ascertain if Minnesotans are involved.

On May 25, when Moner Mohammad Abu-Salha died in a suicide attack in Syria, the FBI stepped up its investigation of youths in the Somali community in Minneapolis. Many now believe the FBI is focusing heavily on their activities, including wiring money to relatives in Somalia and Kenya. Many Somali-Americans, such as those involved with the Somali Citizens League, say they have not been contacted by the FBI to discuss the missing young people — the group that allegedly included Abdi Mohamed Nur — who disappeared from the Twin Cities.

“They [the FBI] have not contacted me, but they have contacted a few in our community,” said Afyare. “My message to my community is to cooperate with the authorities because it is our interest to help them if there is such a case. … Our kids are missing, we’ve not seen it [the community’s cooperation with the FBI] — none of it — yet.”

Loven, however, explained to MintPress that Nur’s case is part of an “active investigation,” and therefore, details of the case can not be discussed. He said the FBI is working with the Somali community in a “collaborative effort” to address the issue.

Pressing questions, but so far, no answers

Federal law prohibits American citizens from taking up arms in foreign countries. The law also bars citizens from joining militant and terrorist groups in any part the world. As the list of young people leaving the Somali community in Minnesota to fight foreign wars continues to grow, many are still wondering what could compel their children who were born or who grew up in the U.S. to leave home to join militants and terrorist groups overseas.

Talking to Somali-American organizations, many describe a cold feeling and uncomfortable relationship among many members of the community. They say the authorities now monitor their mosques and activists without addressing the reasons why their children are leaving: lack of resources; high unemployment rate; and a dearth of social and educational programs.

The community is concerned and wants to know who is recruiting the young Somalis to engage in foreign wars. Somali-Americans say they do not know who is luring the youths to join terrorist groups, but strongly believe that a lack of opportunities plays a major role.

“The high alarming rate of unemployment — the worst in more than ten years — and a lack of investment in the community is the problem,” said Abdirizak Bihi, director of the Minneapolis Somali Education and Social Advocacy Center.

He also noted that the young Somali-American population is growing, but there are limited resources for engaging them.

“Somebody is mentoring them in the wrong direction,” said Bihi, whose organization has tried to provide such engagement for six years, requesting funds for after-school projects, but hasn’t received any assistance. “We can’t do anything, we have used all our resources.”

Shaikh, the Canada-based Muslim scholar, said that those who join the extremist groups do so because they have relatives or friends who have also joined. It’s in those networks where he believes recruitment occurs.

Meanwhile, although there is suspicion that most of the youths are influenced by mosque preachings, Bihi disagrees and says this can not be confirmed.

Though the FBI is working with the Somali community and seeking information, it is still difficult to determine the links in the “terror pipelines.” The pressing questions about who is recruiting the Somali youths from Minnesota to join al-Qaida affiliate al-Shabab in East Africa and the Islamic State in Syria have not yet been answered.

Abdimalik Askar, a candidate for state representative, told MintPress that most of the young people who left years ago surprised their parents, who, like many other Somalis, just want their children to learn about their muslim faith and be religious. When parents and family members learned that the young people had travelled abroad to fight, he said, they were puzzled and couldn’t find help.

“We want to know what they [teenagers] were learning in the mosques. They [parents] never saw that,” said Askar. “Who is behind this [recruiting young Somali-Americans] is the million-dollar-question? We never find the answer.”

Askar, also a doctoral student in leadership and education, added that the young Somali-Americans were sent to study the Quran in a few mosques in Minneapolis. The community was devastated to learn that some had abandoned the community to fight with al-Shabab.

“They are to be very careful and we’ll open our eyes. We want the children we bring to the United States to be able to learn. They need to be engineers, doctors, etc., and not go back. Though it is difficult to raise children in the U.S., we don’t want to lose anyone for nothing.”

Source: MINTPRESS

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar