Somali toddler’s last breath in death camp

Written by: Frank Nyakairu (Reuters)Â DADAAB, Kenya – “Is it too late?” a medic asked while pressing little Anfac’s bony chest. Fluid dribbled from the toddler’s mouth as the medics worked frantically to save her.Â

Tension filled the little room at Medecins Sans Frontieres’ (MSF) only clinic in Kenya’s Dadaab camp – the world’s biggest refugee camp. Anfac’s listless body did not even respond to an adrenaline injection.Â

A minute or so later the medics declared the 2-year-old dead. Her father Anwar Mohammed stood motionless, gnashing his teeth and staring at the malnourished corpse of the daughter he would never see grow up.Â

He had rushed Anfac to the MSF clinic near their makeshift home on a donkey cart ambulance after she failed to respond to treatment at another centre.Â

“In Islam, we believe that when everything fails to cure someone, then it is their time to die,” Mohammed told me after burying his daughter.Â

Forty-eight hours in Dadaab and I am convinced that this is one of the worst places for anyone to be born and die.Â

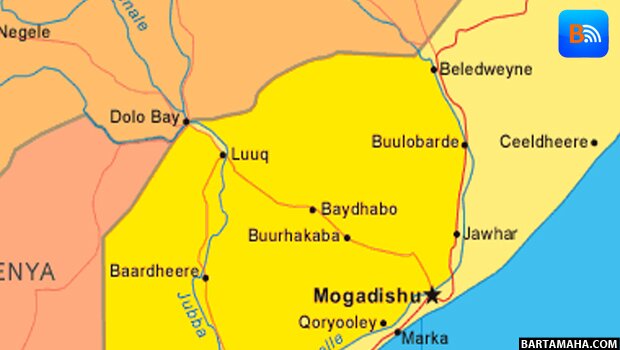

Dadaab in northern Kenya is home to a quarter of a million people who have fled violence in neighbouring Somalia. They live crammed into a few hundred hectares of dry scrubland infested with disease, snakes and scorpions.Â

I had visited MSF’s clinic in Dagahaley, one of three camps in Dadaab, to report on conditions there. Shortly after arriving I found myself watching Anfac slip away. It reminded me how cheap life can be in a senseless war like Somalia’s.Â

Anfac was born to a Somali mother and an Ethiopian father in Ethiopia’s Ogaden region which borders Somalia. Her family fled clashes between Ethiopian troops and Somali militias in 2008. For now, Dadaab is their home.Â

SCORPIONSÂ

Every week thousands of new arrivals continue to swell the camp’s population. But Dadaab is far from safe – disease and other dangers are rife.Â

“Children are dying of preventable diseases here, where if detected early, lives can be saved,” said Andrea Riedel, an Australian MSF doctor.Â

Water and sanitation services in the camps are also dangerously scarce.Â

Some residents in Dagahaley survive on as little as three litres of water a day. Poorly maintained and insufficient latrines increase the threat of epidemics.Â

Residents fear that with the rainy season around the corner, the camp’s shallow pit latrines will overflow, raising the threat of a cholera epidemic.Â

Rains bring other problems too. “As rain water flows into holes in the dry land snakes come out. We treat at least one snakebite every day,” said MSF’s liaison officer Abubakari Mohammed Mohamud.Â

Then in the dry season, residents fear to venture out after dusk because of scorpions. “Because it is too hot, scorpions hide during the day and at night they come and that is when most people suffer stings,” said Mohammed. MSF says it treats an average of 25 scorpion stings a day in Dagahaley alone.Â

But amid all the grimness there is a small source of hope in Dadaab – there are 18 schools in the camp attended by 43,000 children. The sight of bare-foot children walking to school every morning lifts the spirits.Â

Sadly, there is little beyond school. And many teenagers end up on the streets, spending the nights at roadside shelters chewing khat – an addictive leaf which raises levels of aggression and is blamed for some of the violence in the camp.Â

For Bashir Ahmed Bhihi, who has been in Dadaab since Somali dictator Siad Barre was overthrown in 1991, the refugee camp is akin to a jail.Â

“My son was born here. He has finished his secondary education now but that education is completely useless here,” Bashir told me.Â

“He cannot get a job anywhere. He is neither Somali nor Kenyan. He was born in this prison, and I am afraid he will die in this prison.”

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar