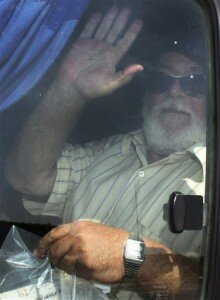

Egyptian fishing boat owner Hassan Khalil, whose crew overpowered pirates off the Somali coast, waves from a bus after arriving back to a hero's welcome by family and friends at the airport in Cairo, Egypt Tuesday, Aug. 18, 2009. The fishermen on Khalil's boat, the Momtaz 1, and another vessel rose up against their captors and succeeded in killing two of them, taking the rest hostage, though Khalil's role is unclear and he may have hired Somali militiamen to help free his men. (AP Photo/Ahmed Ali)

Mohammad Salah (Dar Al Hayat) In light of the Arab contradictions on many levels, it has become normal for us to follow the verbal campaigns between one Arab state and another, or between the media outlets in this state and the newspapers and television stations of another one, or between public figures belonging to an Arab state and the stars of politics, economics, culture, art, or sport in another country. This is what we witnessed, and will continue to witness in the future because the causes still exist. But what is of note is that this state of conflict is present and is blazing inside the majority of the Arab states themselves, among the groups of every society and its symbols and public figures, or among its active or inactive groups.

Let us take for example what is currently going on in Egypt, in terms of the repercussions of the issue of the Egyptian fishermen who managed to flee from the grasp of the Somali pirates last month. They returned to their hometown, bringing back with them some Somali pirates as hostages. If we were in a different era, this event would become a reason for a country with the size and weight of Egypt to pride itself with it. In addition, the fishermen would become stars, streets would be named after them, and their pictures would be mounted in public places. But because times have changed, situations have been altered, and contradictions have exploded, what happened after the comeback of the fishermen and Somali hostages was different. For instance, each side started to manipulate the issue of the released fishermen in its favor. The boat owners appeared on satellite channels and talked about the heroism of Egyptian official apparatuses that planned, supported and implemented the liberation operation without being there, and managed to release the fishermen and abduct the pirates. Official Egyptian officials also appeared [on television stations] and spoke in a different manner, without attributing any victory to themselves or to any official apparatus. The opposition forces also took part as the opposition-affiliated newspapers opened their pages for the fishermen to fight each other. The owners of the boats also turned from two heroes to secondary [figures], to the extent that some newspapers accused them of collecting money to pay a ransom for the pirates, and that they seized the money. Thus, the event, around which the Egyptians were supposed to rally and be proud of, turned into a battlefield between the Egyptians on the pages of newspapers and TV screens and unions.

This is only a simple pattern of events that take place every day. Whenever a certain incident occurs or a certain problem is provoked, or a certain story blows up, various Egyptian sides start a fight over it. The debate and conflict over issue of the candidacy of the Minister of Culture Farouq Husni for the UNESCO director general post does not differ from the Egyptians’ conflict over the issue of the fishermen and pirates. Mixing up between the personal hatred of Husni and the hope to achieve a victory for Egypt in various fields has become a normal thing. Those who have long hoped to snatch the portfolio of the cultural affairs from Husni’s hands were the only one who did not take part in the conflict, as they wished he would win [the UNESCO post] so that he leaves his seat in the cabinet which he has been holding onto for 22 years.

The state of conflict in the Egyptian society goes beyond normal, perhaps because Egypt is a large country with a huge population. But the size and population should be reflected on the Egyptians in the event of a conflict, rather than becoming factors for rift and conflict. In this case, the conflict or the agreement would take place over the country’s interest.

Beyond no doubt, life’s pressures might sometimes get to the nerves of the simple citizens who shoulder the livelihood burdens and the government’s misconduct. But what is noteworthy is that the public is on the lookout for the elite and that the wealthy and educated people are more likely to fight with each other or with the less wealthy and less educated groups.

Therefore, those who are supposed to regulate the rhythm of society in Egypt are those inflicting damages on their societies the most. But the “poor” simple people deal with this or that issue with indifference. Despite their suffering, they believe that those stirring up the conflicts want to also deprive them of happiness. The released fishermen who returned with the hostages turned in the eyes of some sides into pirates who abducted some Somalis.