With local help, Somali refugee joins family in Canada 18 years after separation

EDMONTON It was the happiest of endings, and the happiest of beginnings.

EDMONTON It was the happiest of endings, and the happiest of beginnings.

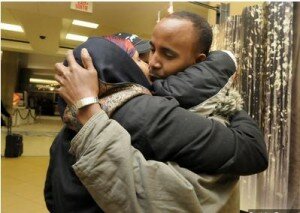

While most of Hamilton slept in the early hours of Tuesday, a family’s wish was coming true at Edmonton International Airport.

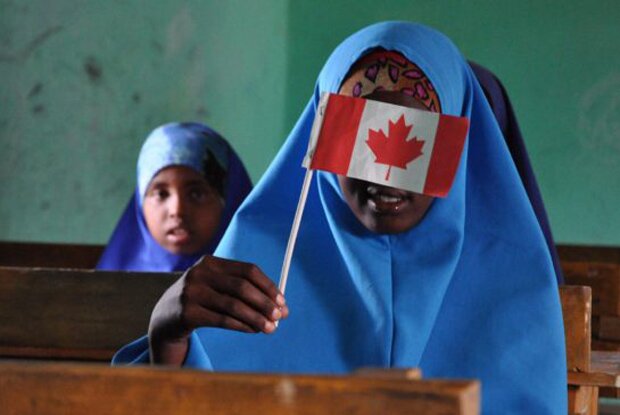

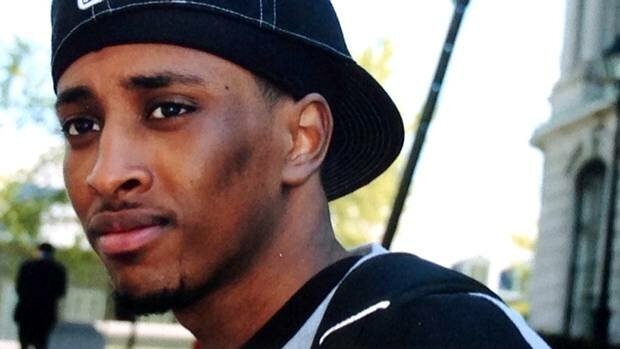

There, the first sight of a thin, pale and exhausted Somali refugee drew tears and hugs from the mother and siblings who have waited 18 years to be reunited with him — since their country’s never-ending civil war ripped their family apart.

Then he was a boy. Today he is a man. He spent more than a decade believing they had been killed. His younger sisters and brothers grew up thinking he was dead.

Noor Hussein Rage appeared overwhelmed as his mother stroked his face with trembling fingers, saying, “happy, happy, happy,” while one sister and two brothers wrapped their arms around them just before midnight, local time.

“I’m elated. I can’t express with words this happiness,” Noor said. “I thank everybody who participated in this process to give me the chance to come all the way to Canada to be with my family members.”

Noor’s family has been living in Canada since May 2004.

Here, they found safety, education and new hope after surviving a decade in the dusty, crowded and sometimes dangerous camps close to the Somali border in Dadaab, Kenya.

Now the world’s largest refugee settlement, the complex of three huge camps continues to swell as new spasms of violence drive more victims from their homeland on the Horn of Africa. The camps were designed for 90,000 people. Today there are 280,000.

Like other refugees at the camps, Noor’s family had lived on meagre rations of dried corn and vegetable oil, and slept in flimsy homemade shelters.

Noor was just 12 on the day he was separated from his family. It was 1993 and the war was in its third year when he went out to work in the field with his father, Hussein. Noor’s mother, Halimo, was at home with her seven younger children, all 11 and under.

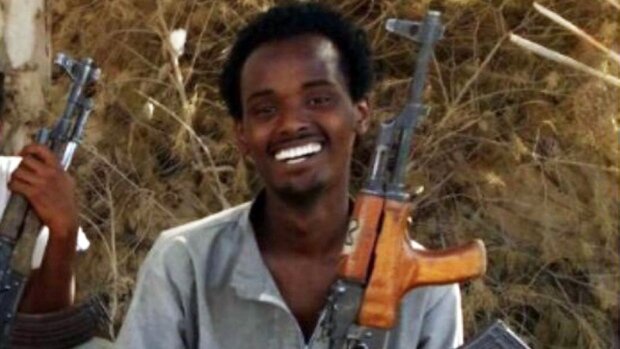

That day, looters drove into their community of Jamaame near the Indian Ocean and started firing machine-guns, killing and stealing at will as they roved over the landscape.

Noor’s father told his son to wait in the field while he investigated. Hussein had nearly reached home when he was shot dead in view of his wife and younger children.

The boy in the field had no idea what was happening to the rest of his family. All he could hear was shooting and screaming. He hid, then ran in the other direction, and lived on leaves and grass and the occasional piece of bread from strangers.

For nearly a year he wandered, willing himself to survive until he felt it was safe to return to his village.

A man took him in and helped him learn English in exchange for work. So many had been killed that the man didn’t know who was alive and who was dead, including the rest of Noor’s family.

Halimo and her children had been spared but could not risk searching for Noor’s body before they fled, taking a circuitous route that eventually led them to the camps at Dadaab.

Years later, when conflict returned to Jamaame, Noor walked to the camps, alone, in search of safety, still not knowing that his family was alive. Shortly after arriving, he learned he had missed them by mere months.

They had been resettled in Hamilton, in an experiment by the United Nations and the Canadian government that moved about 400 low-caste refugees from the camps.

By the time he reached Dadaab, Noor was 17. Had he been 16, he would have been counted as a dependent child and immediately reunited with his family in Canada. Instead, he stayed with an uncle and cousins in the camp, where he and his cousin Ahmed taught English to other refugees.

By coincidence, that cousin would be appointed as translator for a reporter and photographer from The Hamilton Spectator who were working on a newspaper series about the Somali refugees.

Ahmed introduced Noor, who was desperate to send his mother and siblings confirmation that he was alive and healthy. It was late 2005. They had heard rumours that he had survived, and later had confirmation from an official source, but there had been too many stories of identity theft and other problems for his mother Halimo to risk believing it fully.

Back in Hamilton, when she saw the photographs of her son from the camp, she finally believed it was true. He was alive.

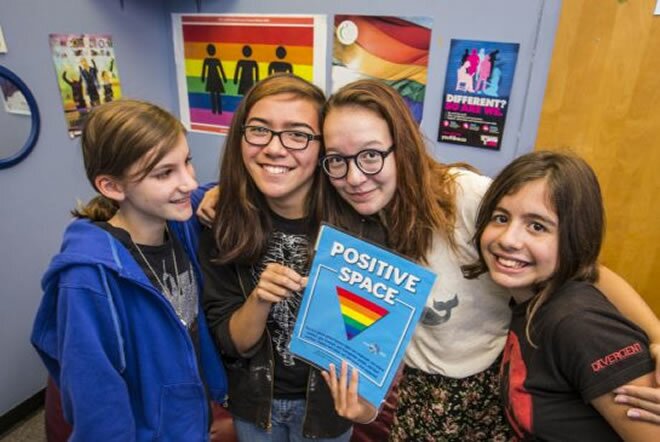

At the time, members of East Plains United Church in Burlington were helping Noor’s family adjust to their new life in Canada.

The church offered to act as Noor’s sponsor, putting its name, its money and international connections behind the application, giving it weight, if not much speed.

The church continued the work after Noor’s family moved to Edmonton in 2006, where most of the siblings, now in their 20s, have found work in the oil industry. Edmonton’s Pilgrim United Church readily agreed to become part of the sponsorship bid.

Back in Burlington, John Durfey, a lawyer and member of the congregation at East Plains, handled most of the paperwork — a file that has grown to 25 cm thick in the five years since the process started.

In January, when he announced Noor had finally been approved for travel to Canada, Durfey said the entire congregation applauded.

“It can be frustrating, but you know there’s a real live person on the other end of this communication, waiting, and is really dependent on you, frankly, for their plight,” Durfey said. “It’s quite rewarding to know that although there are thousands of people out there in this situation, at least you’ve helped one.”

By the time he arrived in Edmonton, bearing a suitcase marked with his long file number, Noor had been travelling for two days and was exhausted.

After the kisses and hugs — a reunion that had even strangers wiping their eyes — Noor’s younger brother, Abdulkadir, 26, who now builds scaffolds in the tarsands near Fort McMurray, handed him a Tim Hortons coffee. A triple triple.

“Welcome to Canada,” he said with a huge smile. “It’s one of our happiest moments in the world.”

905-526-3254

'; if (error != 'Check the following error(s): ') { document.getElementById('divError').innerHTML = error; return false; } captcha = TD.md5.hex_md5(captcha); var updateParam = param + '&title=' + escape(title) + '&comment=' + escape(comment) + '&username=' + escape(userName) + '&email=' + escape(email) + '&captcha=' + escape(captcha) + '&currcaptcha=' + escape(currcaptcha);

updatectl00$ctl00$Content$CPH_Main$ctl02$TrueTemplate0$UserRatingComments2(updateParam); return false; }

function ctl00_ctl00_Content_CPH_Main_ctl02_TrueTemplate0_UserRatingComments2ToggleCommentForm() { jQuery('#ctl00_ctl00_Content_CPH_Main_ctl02_TrueTemplate0_UserRatingComments2_dvComment').toggle(); jQuery('#ctl00_ctl00_Content_CPH_Main_ctl02_TrueTemplate0_UserRatingComments2_hplComment').toggle(); jQuery('#ctl00_ctl00_Content_CPH_Main_ctl02_TrueTemplate0_UserRatingComments2_hplOr').toggle(); jQuery('#ctl00_ctl00_Content_CPH_Main_ctl02_TrueTemplate0_UserRatingComments2_hplCommentAnLogin').toggle(); return false; } // ]]>

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar